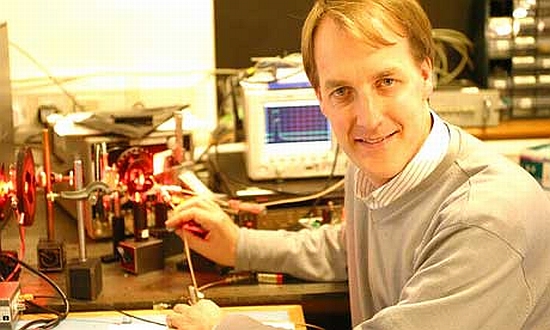

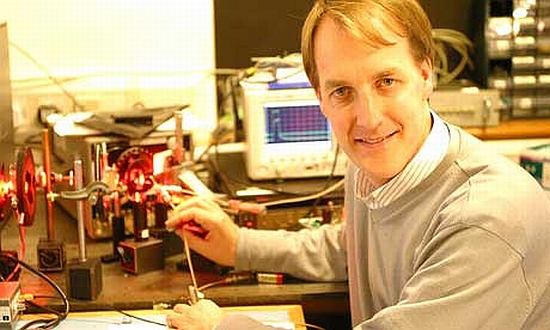

Cambridge University’s Cavendish Laboratory’s physicist Neil Greenham has conceived of an organic solar cell that doesn’t use expensive silicon. Let’s first take a look at how conventional solar cells work. Conventional photovoltaic (PV) solar cells are made from a thin slice (around 200 microns) of silicon that is doped with chemicals to form a bilayer structure called a p-n junction. When photons of light are absorbed by the silicon, electrons flow, creating a small electric current. An organic solar cell takes a similar approach but uses an ultra-thin (100 nanometre) film mixture of two semiconducting polymers instead. The world record for silicon solar cell efficiency – the conversion of light energy to electricity – is more than 40%, but standard cells are between 10% and 15%.

While organic cells fall well short of that. Greenham admits that it’s less efficient than the solar cells used in calculators by a factor of three or four. But he is positive that he would be able to improve on it. However, its much lower making-price compensates.

Greenham’s hand-sized solar cell produces enough power to run an electronic calculator. The idea of a purple-coloured polymer acting as a conductor instead of plastics seems odd. But mounted on glass, this solar cell uses the same class of materials as the polymer light-emitting diodes: long-chain plastics with double bonds which permit electron flow.

Greenham says that it is only incidental that the solar cell happens to be eco-friendly.

He is presently chasing the 5 million pounds worth target of delivering the solar cell, deploying more than one gigawatt of organic PV by 2017 to make carbon dioxide savings of more than 1m tonnes per year.

To add to it, the scientists want to “print” solar cells with an ultra-thin mix of two semiconducting polymers on a flexible plastic backing up to one metre wide. Unlike high-energy silicon manufacture, this will be a cheap low-temperature process for a small carbon footprint.

Greenham mentions that the first type of products might be solar cells in consumer electronics, maybe built into the top of the user’s PDA, laptop or iPod.

Professor Paul O’Brien of the University of Manchester who has been involved with solar cells for more than 20 years has full faith in the new technology. Led by O’Brien and Professor Jenny Nelson at Imperial College London, a £1.5m Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council project is trying to do just that. Its target is a mass-produced hybrid solar cell with energy conversion efficiencies approaching 10%. The first laboratory prototype will be assembled next year.

Explaining the mechanism of the innovative technology, O’Brien says that they are very interested in solar cells where they can take an organic layer that’s printable or sprayable containing an inorganic material like lead sulphide which will actually do the photon capture. Photons knock out loose electrons, which then flow through the cell to produce electricity. Lead sulphide (PbS) adds a new twist to silicon-free solar cells by using nanotechnology. The lead sulphide will be in the form of nanorods, 100 or so nanometres long and 20 by 20 nanometres in section. (One micron is 1,000nm.) When photons hit the rods distributed within a semiconducting polymer, electrons are released. Researchers also plan to use equally small “quantum dots” to achieve the same photovoltaic effect.

Greenham and O’Brien whole-heartedly believe this would be a great substitute for fossil fuel, which is plaguing the world and its environment with its toxins.

Via: Guardian