Amy M. Youngs creates mixed-media, interactive sculptures and digital media works, that explore the complex relationship between scientific knowledge and nature. I know this is fairly incredible in itself but what is more remarkable is the use of electronics, kinetics, sound, insects, plants and pixels she employs in order to create an art about the complex relationship between technology and our changing concepts of nature and self.

She has exhibited her works nationally and internationally at venues such as Springfield Museum of Art (Springfield, OH), Pace Digital Gallery (New York, NY), the Biennale of Electronic Arts (Perth, Australia), John Michael Kohler Arts Center (Sheboygan, Wisconsin) to name a few. Though she has a very hectic schedule but some how she managed to answer a few of our queries, which we are presenting before you in the form of an (email) interview, which goes as,

1. Amy, please give us your brief biographical sketch?

Amy: Hello and thank you for your interest. I’m an artist who is working with biology and technology as media to explore our conflicted and changing relationships with the natural world. My work is often interactive; designed to elicit dialogue and first person reactions from viewer/participants. I use technology as a tool for human engagement and re-enchantment with the natural world. Rather than try to support myself with this less-than-saleable type of artwork, I work as a professor of Art and Technology at the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio.

2. How are you able to explore the complex relationship between technology and our changing concept of nature and self? Also, how far have you been successful in communicating between nature and humans?

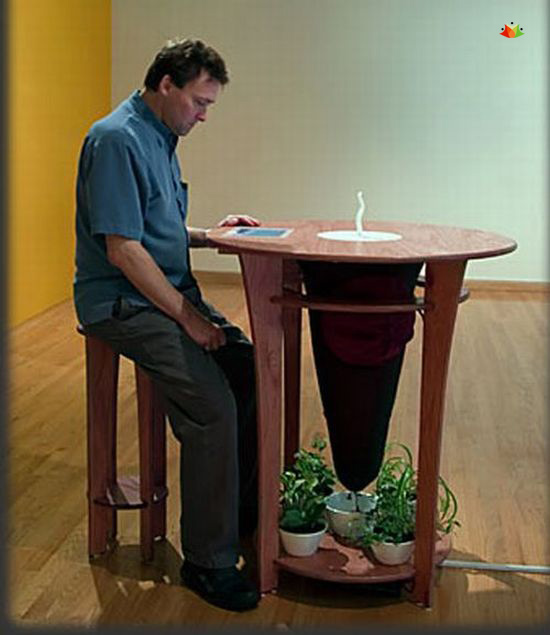

Amy: I try to do this through artwork – perhaps better described as projects – that connect humans to the non-human world. Some of these attempts are ironic, some are quite sincere and others are failures, but all are designed to get people thinking about their connections and relationships. For instance, with the Digestive Table project, I wanted to explore the cycle of food waste, decomposition and reconstitution as fertilizer in a self-contained system that people could relate to, so I constructed a dining table with a built-in worm composting system that can be observed by humans as they eat their food. They can dump the leftover parts of their meal into the portal at the top to continue the cycle and to become a part of it. Even though we may not be able to talk to the worms, we can “communicate” with them in a sense, by feeding them.

3. What made you come up the concept of Intraterrestrial Soundings?

Amy: I have had composting worms for about 15 years. Even though I have moved from San Francisco, to Chicago to Columbus, Ohio in that time and am not always very good at remembering to feed them, their little ecosystem in a plastic bin has persisted. I am amazed with their resilience and ability to process my leftover food and shredded paper waste into rich fertilizer. They operate in the dark and I was curious about learning more about them, so I figured out how to amplify their world in ways that I – and other humans – could perceive them. Very sensitive microphones are embedded into the soil with the worms and the signals from the worms moving about are fed to a multi-channel digital amplifier which sends the sounds into 8 small guitar amplifiers that are embedded into a worm-shaped couch. The human participant can lie on the couch to hear and feel the sounds of the worms moving inside the dark wormbox. Because people were not sure that the worms were in there, I included an infrared camera which would not disturb the worms (they do not like visible light), that sent a live video image of the worm activity to a projector focused onto the ceiling above the couch.

4. Like Prototypes for Hermit Crab Shells, are you planning to create more prototypes?

Amy: This project is an example of a failed attempt to design for animals, as the hermit crabs rejected all of the rapid prototyped shells I made for them. Ultimately, I was happy to learn from them. What makes me think I can intuit the desires of a hermit crab? Nevertheless, I enjoy the pursuit and I was inspired to learn more about them and it helped me to respect the wisdom of evolutionary design. One of my hermit crabs did eventually move into a clear glass shell that was constructed for him. This was exciting, but kind of sad because I could see it was too heavy for him to carry around. He moved back into a natural shell the next day.

Though I am no longer working on this project, I do continue to make other types of prototypes. I actually think of each of my projects as prototypes, because I know they can always be improved upon.

5. What according to you is the future of cloning and micropropagation technologies?

Amy: These technologies are commonly used to produce plants. We enjoy the fruits from cloned trees on a regular basis. Now even animals, in the form of pets and livestock, are being cloned, but this is too expensive and ethically problematic for me to want to participate in.

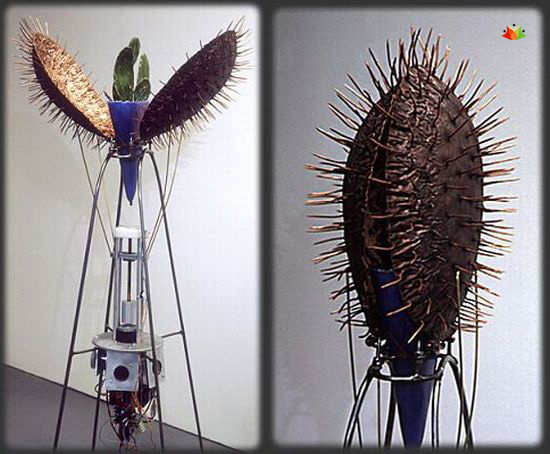

6. You have been trying to project life/feelings in your projects like Engineered for Empathy, Hyperdomestic Cacti, Rearming the Spineless Opuntia. How far have you been successful in meeting your goals?

Amy: Even though the plants inside these techno-sculptures may not have feelings in the same way that humans do, they are alive and they deserve care and respect. The technology is designed as a frame to help us see them as an integral part of our world. When they have been exhibited, people ask me many questions about the plants, which makes me feel that the projects are successful. With the “Rearming the Spineless Opuntia” sculpture, people wonder about how a spineless cactus came to exist and they are not often aware of the human hand in the development in plants like this. They wonder if the machine I have built for it will really protect it, they wonder about other more effective ways to protect a spineless cactus and they wonder whether it is our job to protect a cactus.

7. What is the difference between the concepts of Holodeck for House Crickets and Cricket Call?

Amy: These projects are both environments for appreciating living house crickets. The first one I made, “Cricket Call” is focused on facilitating dialogue between humans and crickets. Humans can speak into a telephone that projects their voice as electronic chirps into the glassed-in cricket house. There is a tiny human-like living room with cricket-sized furniture that the crickets live in, designed to frame the crickets in a way in which humans might appreciate them. The tiny television shows a live image of the human on the telephone, to bring them into the scale of crickets. The possibility of interaction is facilitated through technology, and even though it is unlikely that the crickets can decode our electronic chirps, people are able to see crickets up close and more personally than they usually do.

What makes the “Holodeck for House Crickets” quite different is that it is only interactive for the crickets. Humans can view, but not activate the video a prairie that is projected onto the glass bubble the crickets live inside of. Only the very high-pitched chirping sounds of crickets cause the video to move. It was interesting to think about what domesticated crickets might want to view in their own Holodeck. Even though they are domesticated house crickets, it seemed like they might enjoy a moving panoramic view of a natural environment, so I made a video of grasslands at cricket-eye view for them to watch and interact with by chirping.

8. Amy, please make our readers aware of your Hydroponic Solar Garden?

Amy: This project is a collaboration with my husband, Ken Rinaldo and it was the result of our discussions about growing food indoors in our home, rather than purchasing vegetables and lettuces that are trucked in from far away. We wanted to reduce our carbon footprint, but also to make a beautiful sculptural waterfall for our home. We were fortunate to have an artist residency at Pilchuck Glass School, where we worked with expert glass artists who could make the fantastic shapes we designed for the hydroponic plants to live in. The pump to draw water up to the top of this vertical garden operated from a small solar panel. We are very happy with how beautiful this piece is, but we have also learned about the impracticality of it as an indoor garden. Now we are working on a more practical version.

9. Don’t you think that practical application of Digestive Table is a little difficult especially the idea of watching worms while eating, not that many people would choose to take their meals this way, what do you have to say in this regard?

Amy: Even though the worm-surveillance-TV part of this project may not be appetizing to all, this project is actually quite practical, since it allows for food disposal, composting and fertilizing all in one single table. Actually, watching the worms on the tv screen is quite relaxing, since they move very slowly. I think it is even pleasant, compared to watching network television while eating. Part of my goal with this project was to get people’s attention with the idea that they could watch worms on closed-circuit television while eating, but it was also to demonstrate the fact that worm composting does not smell bad, even when happening right under your nose.

Surprisingly, I have been contacted by people who want to sell this artwork as a manufactured product.

10. May we have the honor of knowing your future plans? And presently, what are the interesting things that have hooked your attention?

Amy: Yes, I am very excited about a new collaboration with Ken Rinaldo called “Farm Fountain”. We have continued to pursue growing vegetables hydroponically, but now we are using 2-liter soda bottles as planters and also growing fish in this system, which serve to fertilize the plants. It is currently a prototype edible ecosystem set up in our studio, but we will be constructing a larger version for an exhibition organized by the Natural World Museum.

We are both very excited about the potential for this project to have an impact beyond the units that we construct. Our goal is to get other people excited enough about it to want to make their own. We have posted the plans for building the home version of this project on our website, Farmfountain because we envision this as an open-source design that other people can build themselves and improve upon.

11. Finally I’d like to have your say on our Ecofriend.org?

Amy: I love the optimism and ingenuity being shown on Ecofriend.org. How can one not be excited about a pedal-powered snow blower made out of recycled materials and the harnessing of solar power from spinach?

This is indeed a wonderful interview, thank you Amy for sparing out time in doing a rendezvous with us, it is greatly appreciated.

Before signing off, I’d like to wish you luck for all your future endeavors and I’m looking forward to more creations coming outta your vault 🙂